[1/10] How to build a growth model

Understanding 3 parts of turning your business idea into a growth model

Structure of the series

Welcome to the first essay of the 10-part series on Growth called Firestarter. The series is structured in 3 sections:

The first section, with 3 essays, is going to be focussed on how to plan growth,

the middle section, with 4 essays, on functional execution, and

the last section, with 3 essays, on managing different aspects of it.

Why start with planning growth, instead of, say, jumping directly into 101 ways to hack growth?

Growing a business is akin to a journey that you are about to undertake. The first section then is about the preparation you do for the journey – preparing the itineraries, bookings you make, packing the essentials, and so on. After all, paraphrasing Lewis Caroll, if you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.

Further, the first section on planning is divided into three essays:

First one, i.e. the article below, is focussed on how to put together a long-term model for the project,

the second one on how to prepare a short-term roadmap, and

the third one on how to put in place a continuous measurement system to keep track of the project.

Back to the travel metaphor to understand the breakdown: the first essay is about putting together a map of the territory you will be heading into. The second essay is then about highlighting the specific route that you will be taking within the map. The third essay is learning how to use a compass to know if you are on the right path or not.

How to get the best out of this series: treat it like a workbook

One final thing before diving into the article itself: a tip on getting the best out of this series. While going through this essay, have a specific business in mind. And, instead of passively reading, keep applying the concepts to that business to really internalize them. The articles will have regular prompts to remind you to do so.

The business can be an idea of yours that you intend to start up. Or it can be a project you are working on professionally. Or it can be some famous company that you want to analyze as a case study (but hopefully the first two, since you will have some skin in the game to go deeper).

Alright! Without further ado, let’s get started.

The Growth Formula

Wait, did you think of a project? If yes, answer this question: is that business a woolly mammoth hunter or a bee farmer? That is to say, does it have a few but very big-ticket customers, or does it have a lot of small-ticket customers? Or is it somewhere in between?

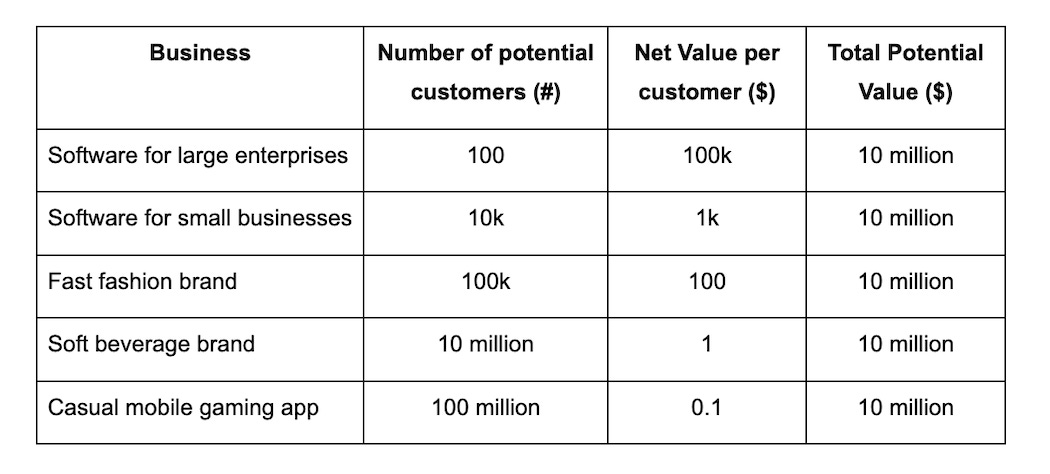

Consider the table below:

Your project could be on the woolly mammoth hunter end of spectrum: having just a hundred customers but all of them potentially worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Or, it could be on the bee farmer end of spectrum, having millions and millions of customers and all of them contributing in cents. Or, somewhere in between? What matters is the product of the two.

Quantitatively, this idea can be put thus:

Potential value of business = Number of potential customers * Net value per customer

This forms the bedrock of everything that is to follow in this article, and we will keep referring to it as ‘the growth formula’. (Note that I am using the term value for the output of the formula to keep things simple but, to be clear, the formula’s output is not revenue or valuation. Having said that, the three concepts are closely linked and I’ll come back to link them all later in the essay.)

Now, let’s use this formula to calculate the potential value for the project you have in mind. Starting with the first part: number of potential customers.

Estimating the Number of Potential Customers

To estimate the number of all potential customers for your business, you should first know one of them in detail. Or, in marketing terminology, you need to know the “ideal customer profile” for your business. A concrete profile can be in terms of:

Basic Demographic attributes: age, gender, location

Advanced Demographic attributes: Education level, family size, occupation, income, etc.

General behavioral attributes: habits, interests, attitudes

Behavioral attributes specific to the category your product/service is operating in: e.g. attitude towards sustainability if that’s a core proposition of your product.

Once you are clear on that one ideal customer, you can then proceed to estimate how many similar potential customers exist. But how does one do that?

There are different ways to go about it. One is a top-down approach (or guesstimate) where you start with the overall population in the market that you intend to service and keep narrowing down to the customer persona. For example, if you are building a sneaker brand for Gen-Z customers living in metro cities in India who wear sneakers, you start with the population of India, then narrow it down to how many live in metro cities, then to how many of them are in the Gen-Z cohort, and then to how many of them wear sneakers, to arrive at the number.

The other approach would be to look at it from a market category-lens, especially if you are building a company in an existing category. That is to say, in the previous example, you can start with the overall sneaker market size from secondary market research reports, estimate how much of it serves Gen-Z customers in metro cities, then estimate how much of that market you can capture (by looking at the pace at which similar brands historically have gained market share).

If your business will be creating a new category altogether – the way Meesho was creating social commerce as a new category, or WhiteHat Jr was creating a new category of teaching kids to code – one invariably has to follow the top-down route but has to take extra care while defining the customer profile. Defined loosely, often out of optimism, it can make the potential market size look much bigger than it might be. That is, if Meesho defined the core customer persona of resellers as homemakers, but with a background in fashion either as part of educational experience or family business, it would make the potential market much smaller. However, if we had optimistically defined it as any homemaker, or anyone for that matter, with intent to earn money by reselling, the potential market will look much bigger, but the subsequent calculations will be on increasingly shaky ground.

The key point is to keep the ideal customer profile as sharp as possible, and thus the potential number of customers on the conservative side. Without defining the customer persona and your right to win, and just using the method of capturing some share of a large existing market can lead to an irrationally large number. To put it simply, yes, taking away 1% of Nike’s market will make yours a multi-million dollar brand, but the question is: will you really be able to do that? This is what Bill Aulet says in his book ‘Disciplined Entrepreneurship’ about this temptation:

The common pitfall is “The China Syndrome,” also known to my students as “fun with spreadsheets.” Rather than create a new market, the thinking goes, one could choose a huge existing market, get a fraction of the market share, and reap the rewards. After all, if you could get even a tenth of a percent of the toothbrush market in China (population 1.3 billion), wouldn’t you make a lot of money?

I call such high-level market analysis “fun with spreadsheets,” because you have not demonstrated in a compelling manner why people would buy your product or why your market share would increase over time. You also have not validated any of your assumptions by learning directly from customers—you probably haven’t even been to China. After all, if entrepreneurship were this easy, wouldn’t everyone sell toothbrushes to China?

Big companies with lots of resources can afford to work hard to gain incremental market share, but entrepreneurs don’t have the luxury of resources. Don’t get ensnared by “The China Syndrome.” Take your resources and apply them to a narrow, carefully defined new market that you can dominate.

On the other hand, if you are yet to find your narrow market that you can dominate, in order to do a bottom-up estimation, you might have to estimate what % of a sufficiently large, existing category will you be able to capture, to, say, rank possible business ideas. A good rule of thumb could be that market share % should not be more than the number of years it would take to gain that market share (e.g. the new sneaker brand I am building will capture 5% of the sneaker market in 5 years and 10% in 10 years). A larger number would run the risk of making the foundational number, on which the rest of the calculations, and subsequently the growth efforts, are going to be based, too optimistic.

If you wish to read more about this topic, especially how investors and consultants approach it, you can read up on the terms TAM (Total Addressable Market), SAM (Serviceable Available Market), SOM (Serviceable Obtainable Market).

Calculating Net Value per Customer

Now, coming to the other factor in the growth formula: net value per customer. While, the first factor, i.e. number of potential customers, was dependent majorly on the larger market or category, or the niche within a category, that your business is going to operate in, the second factor is more specific to your business model. Let me explain.

Suppose you are launching a new premium clothing label in India. You pay ₹100k to a lifestyle influencer to give your brand a shoutout. From that campaign, you get 100 customers. That’s ₹1,000 spent in acquiring each customer on average. That’s your Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC).

After the first 100 orders, you get an additional 110 orders from these 100 customers over the course of time. So, each of these customers, on an average, has given you 2.1 orders. Now, for each order, suppose you make ₹2,000 in profit, after paying all the operational costs (cost of making the clothing and delivering it being the two major cost heads generally for an online brand, apart from customer acquisition costs). So, you make 2.1 orders per customer * 2000 per order = ₹4,200 per customer. That’s your Customer Lifetime Value (CLTV or just LTV).

Net value from customer then is the value your business got from the customer i.e. LTV minus what you paid for the customer i.e. CAC.

So, for this example, the net value of each customer = LTV minus CAC = ₹4200 - ₹1000 = ₹3200.

And, if you had estimated 100k customers as the potential customer base for this brand, the growth formula becomes:

Potential value of business = number of potential customers * net value per customer = 100,000 * ₹3200 = ₹320 million

You can now see why I said that while the estimated number of potential customers is mostly a function of the market/category size, the net value per customer will differ significantly between competing businesses in the same market and is more specific to your business model. Specifically three things within that:

How efficient is the business in acquiring each customer i.e. CAC

And, within LTV,

Margin you have in every order which is dependent on cost of goods and cost of operations

How many orders does the business get per customer i.e. Retention

In the same example, instead of spending ₹1000 on acquiring every customer on an average, if the business was spending ₹2000, the net value of every customer drops to ₹2200. And the potential value of the business then drops from ₹320 million to ₹220 million.

Or, if instead of getting 2.1 orders per customer, with the same CAC of ₹1000, if the business was getting just 1.1 orders per customer, the value of every customer will drop to ₹1200. And, the potential value of the business, with the same number of unique customers, drops from ₹320 million to ₹120 million.

This point is worth repeating once more: while you can still get away with ‘fun with spreadsheets’ assumptions on the first factor of growth formula, if the assumptions are conservative enough, it is really important to calculate the second factor specifically for your business. How? With real data being generated by your business. That is: How much is it actually taking for your business to acquire a customer? How many times is a customer coming back to buy from your business? How much does your business make per order?

Therefore, the first two orders of business for a growth lead have to be to put together: 1. an ideal customer profile, and 2. net value every such customer is bringing in. If the project is in ideation stage, and the latter number has been calculated using industry benchmarks, it has to be validated as soon as the business becomes operational and first few customers come in.

Turning Growth Formula Into Growth Model

Alright, so you have got a ballpark number for potential customers for your business, and the value every customer is generating. And thus, you have both factors for the growth formula. Now it is time to turn the two-dimensional growth formula into a three-dimensional growth model. How? By adding the dimension of time.

For example, let’s say the business you are trying to model is a fitness app with a potential global market of 1 million customers providing a net value of $10 each, thus giving it a potential value of $10 million. But wait. 1 million customers to be acquired over how much time? All of them to be acquired tomorrow? Or over the next 10 years? And, over what period of time are they providing a net value of $10? In the first month? In the first year? Over five years? (The dreaded ‘over the course of time', or ‘lifetime’ part of lifetime value.)

Adding the pace at which the business will acquire these customers and the pace at which the customers pay the business back (directly or indirectly) is how this simple growth formula will convert into a slightly more complex growth model. Let’s take a look at it, but with a woolly mammoth hunter kind of business instead to keep things simple.

Suppose you have built a really sophisticated piece of software that’s relevant only to 5 companies in the world, but each of whom will pay you 1 million. The growth formula then is a cakewalk: 5 accounts * 1 million per account = 5 million. Now, let’s add the dimension of time to it.

Let’s say that we will acquire only 1 account every year. Acquiring them will cost $1 million each and the annual revenue from each of the customers will be $500k and the revenue will continue for 4 years, after which they will stop using the software. Putting it all together, we get this table:

Now, let’s consider all the accounts. Remember we are acquiring 1 account every year and the contracts expire after 4 years, so account #2 will start in year 2 and end in year 5; account #3 will begin in year 3 and end in year 6, and so on.

Adding them all up:

If you add the net value across all the years, you still get 5,000k or 5 million: the exact same number that we had got from the growth formula (5 accounts * 1 million per account).

However, after adding dimension of time, a new picture has emerged in the growth model. The company is going to be unprofitable in the first year of its operations, it breaks even in the second year, and it therefore would need an external capital infusion to get through the first couple of years. This is where investors enter the picture. But the person/institution giving money to keep the company going needs to know how much the company is worth. Is it 5 million dollars? Or is it some other number? How do we calculate that?

Turning Growth Model Into Valuation Model

A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. That’s kind of what turning a growth model into a valuation model is all about. It is obvious that a promise of a cupcake today is a better offer than promise of a cupcake a week later. But how much better? Is 1 cupcake today equivalent to promise of 2 cupcakes a week later, or is it equivalent to promise of 3 cupcakes, or to a that of a dozen. You get the picture (and hungry).

Without getting into the concepts of Net Present Value (NPV) and Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), which you can read about if interested, the idea is to calculate and know the current value of any future money before adding them.

So, in the previous growth model table, the 500k in year 8 won’t be the same as 500k today, or 1000k in year 7 won’t be the same as 1000k today, and so they can’t be added together. Hence, to value the business, all the future values need to be converted to their corresponding value today, before adding them up to arrive at the valuation of the business. Classically, this would be put as: the value of a firm is the net present value of all its future cash flows.

Now, as a growth lead, while you will probably never be asked to value the business, and it will be left to the functional experts, it is important to at least understand how you go from a business idea, to thinking about who will buy the product, to thinking about potential value of the business, to putting together a growth model for revenue and costs, to valuing the business. And, how all these concepts connect.

This is also a point that will recur through this series: having a cross-functional job like growth lead means knowing just enough in varied fields (analytics, marketing, sales, product management, finance, people management, etc.) to get the core job of growing the business done. And the point of this series is to deliver that minimum knowledge required across such different fields.

Summary

So, let’s recap all the ground we have covered so far:

We picked a business idea

We fleshed out its ideal customer persona

Based on the persona, and/or the market category, we estimated the potential number of customers for the business

We looked at our customer acquisition cost data, our margins in every order, and how often our customers come back to buy from us, to arrive at net value per customer

We added the dimensions of time to turn it into a growth model

And, finally, we got an idea of how growth model can be used to value the business itself

In the next essay, we will start looking at how we convert this bird’s-eye view of a plan to a step-by-step roadmap.

If you have any suggestions on this article, or need any clarifications, I am reachable at sudhanshu@skilletal.com.

Very insightful!

very digestible yet on point, light on the grey cells yet driving home the appropriate points